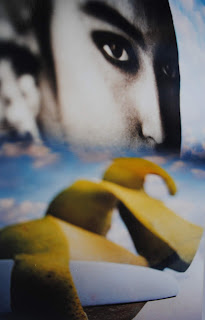

Time-stretched self-portrait by María José Gómez Redondo

Berenice Abbott. Portrait of the Artist as a Young Woman. Negative c. 1930/distortion c. 1950

I was looking for self-portraits made by women artists and found an article in https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/256. A guide to five powerful self-portraits in the MoMA collection

I felt shocked by this. Berenice could not have influenced my work because I did not know her work when I started to do my photos.

This picture gets several things that engage me:

- The photo is the result of two shots: one in 1930 and the other in 1950. It might connect with the concept of Delay in Duchamp.

- The distorted face connects with the combination of various cubism views and distortions in surreal images. The taking of photos also connects with the press images taken by the POP movement, Andy Warhol art, and with the concept of appropriation in post-modernity.

This self-portrait places Berenice in three positions: model, photographer, and spectator of her image. She said about the picture: I like this picture so well because it re-creates some of the feelings I got from the original scene, and that is the real test of any image. Berenice Abbott, 1953.

When I start to do my artwork, I concentrated my interest in photographing photos that I have seen in the press. I believed that art has closely related to the exercise of learning to watch. I soon realized that not far from the image we see, there is another one, which is less stable, which seems to be moving, and I decided to combine them, trying to raise the one which is always left behind, hidden.

The photographer Berenice Abbott chose to distort her face in this self-portrait, a contrarian response to rigid beauty ideals for women. It also evokes a sense of vulnerability in a moment of sweeping technological and social change following World War I.

By warping the paper under the enlarger, Abbott emphasized her eyes that she looks like a cat. Her fascination with the flexible inscription of reality in photography overrode vanity. However, the distorted face is still recognizably hers-described at the time as a face with no edges, boy-cut hair, and kewpie eyes.

We both throw the formal construction of the images posed as related fragments are made very clear. Pieces of paper, transfers on the photographic emulsion, imprints on different supports, I make the image acquire a technical depth in keeping with its visual complexity.

Face, diptych, photography printed over the fabric. 1 m length 1.50 width

María José Gómez Redondo 1999